Two weeks ago, we featured opinions that suggested a “breather” in the Party Going On In the Indian Stock Market. Interestingly, the Indian Stock Market has fallen by 3.25% in the last two weeks and the Indian Rupee has fallen by about 2.3% against the U.S. Dollar. But this is nothing compared to what is happening to other BRIC countries.

1. EM Currency Meltdown

This week’s feature story was Brazil. The Brazilian Real suffered a waterfall decline & the U.S. Dollar soared like a rocket against the Real as the chart posted by @DavidSchawel shows.

The damage extended to the entire emerging market universe.

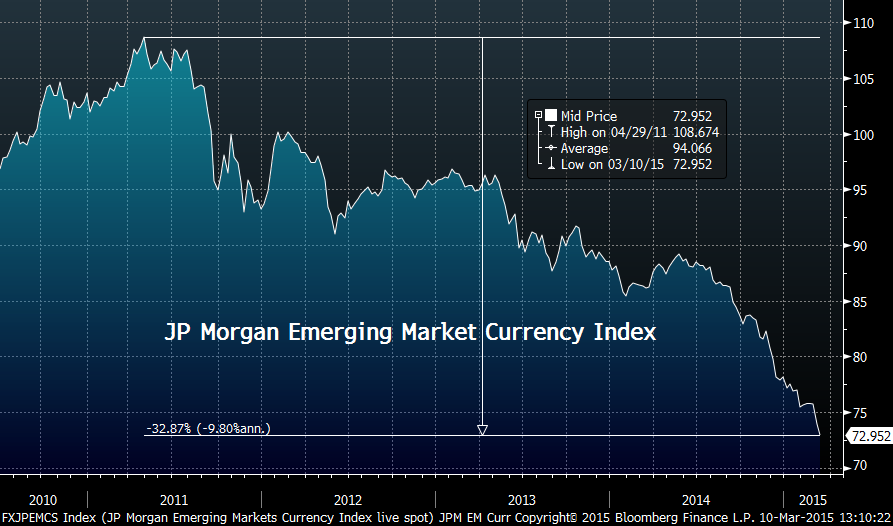

- Charlie Bilello, CMT @MktOutperform – JP Morgan EM currency index at new lows again. Has lost a third of its value since 2011.

2011 was indeed a semi-bubble in emerging markets. That is the primary reason we turned negative on India and on emerging markets in July 2011. Then the primary trends were actually more negative for India than for the rest of BRICS & emerging markets. That is why India became the first “fallen angel” in June 2012.

We felt then that the major trends in EM were about to reverse and opined that “fallen angel” India would be the first BRICS country to fly again. One year later, the Indian Rupee crashed to an all-time low of 68.60 against the Dollar and India was again plunged into despair. But that was an opportunity. We saw a decisive pro-India move in US markets on Wednesday, August 28, 2013 and wrote about it then.

2. Party in the Indian Stock Market

That was the beginning of the party. The Indian stock market rose from 17,996 on Wednesday, August 28, 2013 to 29,459 on February 28, 2015, the date of our Party article. If this beautiful 64% rally is not a party, we don’t know what is. This rally reflects both the underlying micro strengths of the Indian economy and confident expectations of the new Modi-Rajan regime.

But if you look at it closely, you will see an anomaly. Yes, the Indian Stock Market is up to new highs, but the Indian Rupee is still languishing. It remains well below the 56-58 $-Rs band that prevailed before the August 2013 currency crisis. All the confidence in Modi-Rajan and all the euphoria about India’s rise has not been able to take the Rupee above the pre-crisis band. Frankly, this is good because this keeps India cheap and that may be required in this period of global currency wars. But it is also a negative technical judgement about India’s frailty, a concern that the Party may be more about hope than reality, and a deep seated worry that the Indian story could easily be at risk again.

3. Look to Debt Markets

Credit is the foundation of every economy. Debt markets fly when credit becomes abundant and fall when credit or monetary liquidity contracts.

- barnejek @barnejek – The Great Round-Trip in EM local debt. This is the last 5 years of GBI. Return? Zero…

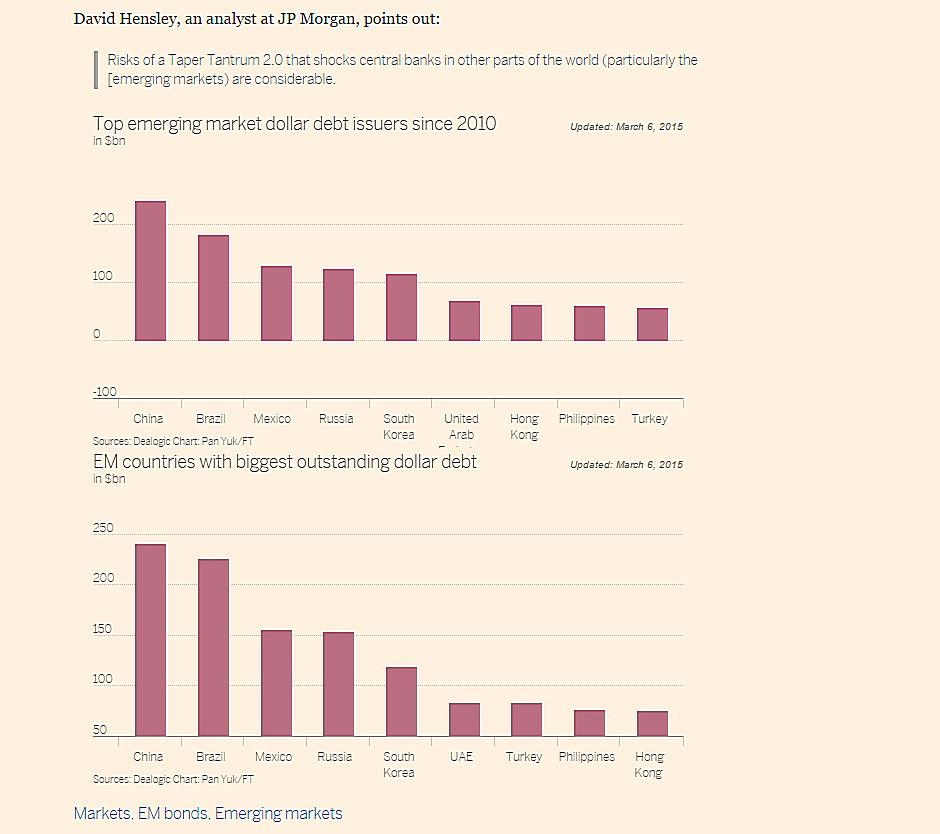

- Top Money Charts @topmoneycharts – RT @MacroPru: EMs face cost of $ surge: 2 charts @fastFT http://on.ft.com/1GxDOUM #emergingmarkets #strongdollar

India is not among these countries. So why should we worry?

4. Why worry about India?

India looks shiny and great now. The steep fall in commodity prices has been a boon for India. The Reserve Bank of India has begun cutting interest rates. And the world is getting even more optimistic about India. This week, the IMF raised its projections of India’s growth rate to 7.2%. What country would not kill for such a growth rate?

But “jo diktha hai wo nohi hai aur jo nahi diktha hai wo hai” was a refrain of the veteran Bollywood actor Kader Khan – what you don’t see is and what you see isn’t. In that spirit, you need to probe underneath India’s shiny economic exterior to find the reality, reality of decay in the infrastructure.

That decay is a steep massive rise of corporate debt. This was discussed in an article in the Hindu BusinessLine on March 2.

- “Government debt has actually fallen as a share of GDP, as has household debt. However, corporate debt has increased and is now as much as 45 per cent of GDP, while debt of financial institutions has also increased in the past seven years. As a result, total debt now accounts for as much as 135 per cent of GDP.”

- “The problem is intensified because much of the corporate debt is concentrated in a few infrastructure sectors (such as power generation and transport) and in the aviation industry, in which investments in the past decade were almost entirely leveraged.”

- “The dominance of corporate debt within India’s debt profile also matters because a highly leveraged corporate sector is less likely to invest, yet much of the current government’s hopes for future growth in the Indian economy are pinned on corporate investment.”

Where does this reside and who takes the fall if India’s corporations can’t generate cash flow to repay the debt?

- “This was done through public sector commercial banks, which — in the absence of development banks proper — were forced to take on risky long-term loans that are now having to be restructured.”

That is the crux of the problem. India’s public sector banks may not have the financial size to absorb this level of restructuring and, frankly, India’s Government may not have the financial capability to put in enough capital to both protect the banks and to provide necessary spending to achieve its growth targets. This reality could prove a problem for the Indian Rupee if the markets begin to focus on it.

Both Arun Jaitley, the Finance Minister, and Raghuram Rajan, the Reserve Bank Governor, know this and they have told the banks to not expect bailout type monies from the Government. The message has been received loud and clear as this week’s story about the State Bank of India shows:

- “India’s largest bank, the State Bank of India (SBI), will hold a record online auction this weekend to sell repossessed flats, warehouses and offices worth a total of nearly $200 million as the state lender seeks to chip away at its $10 billion mountain of bad debt. … The SBI auction will be the biggest nationwide online sale to date and is a rare public move to turn distressed loans into ready cash.”

This auction will take place this weekend. What if the auction proves unsuccessful? In any case, the auction is to get $200 million, merely 2% of State Bank’s $10 billion of bad debt. And the problem is across India’s banking sector:

- “Including both bad and restructured debt, more than a tenth of Indian bank loans have soured. India Ratings and Research, part of the Fitch agency, estimates impaired loans could hit 13 percent of the total by March next year.”